|

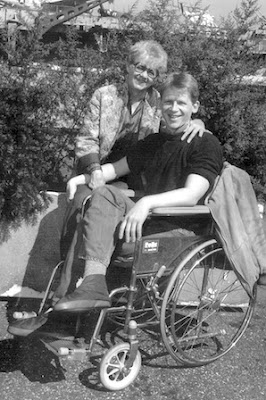

| Imagen: Nita Pippins con su hijo Nick |

At 60, she moved to New York to care for her dying son. Instead of returning home, she dedicated herself to AIDS patients during the worst of the epidemic.

Steven Kurutz | The New York Times, 2020-05-19

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/19/obituaries/nita-pippins-dead-coronavirus.html

One day in 1987, Nita Pippins received a call from her only child, Nick, a 33-year-old actor in Manhattan who was dying of AIDS. “Mom, I’m in bed. I can’t get out of bed,” her son told her. “It’s time.”

Ms. Pippins, a retired nurse living in Pensacola, Fla., put her belongings in a friend’s house, took what she could and moved to New York to care for her son. At age 60, she began an improbable and remarkable second act.

Devastated and ashamed by her son’s AIDS diagnosis, and troubled that he was gay, Ms. Pippins initially kept the illness a secret from her family and friends. And she felt out of place in the big city. On breaks while caring for her son, with whom she had moved in, she would sit inside the Nathan’s Famous restaurant then in Times Square and repeat, “I hate New York. I hate New York. I hate New York.”

But Ms. Pippins nursed her son for three years as AIDS ravaged his body and he went in and out of the hospital. She saw members of the theater group he had founded and residents of their midtown building, Manhattan Plaza, falling sick also. And by the time her son died, in 1990, Ms. Pippins had been transformed.

She became close with her son’s gay friends, and decided to stay in New York. She dedicated herself to AIDS causes. She became a tireless volunteer for Miracle House, a charity that provided out-of-town families of AIDS patients with housing and support.

For mothers working through anger, guilt and sadness, Ms. Pippins served as a parent who had been there. For men estranged from their families, she became a replacement mother, sometimes holding their hands as they died.

“She didn’t come here to be an activist,” said Irwin Kroot, who met Ms. Pippins through her son’s partner, Dennis Daniel, and interviewed her for a possible memoir. “She was filling a void. She was usually with young men who were dying and was, at their request, a go-between for them and their families.”

Ms. Pippins died on May 10 at Amsterdam Nursing Home in Manhattan. She was 93. The cause was complications of the novel coronavirus, Mr. Kroot said.

At a time when AIDS was widely misunderstood and gay men who suffered from the disease were treated like pariahs, Ms. Pippins called on countless families across the country to come visit their children. Often, those parents had little sense of their sons’ lives in the city or how sick they were.

Ms. Pippins would tell them to set aside differences and be present for their child. Some took her advice, some didn’t. Ms. Pippins would meet wary out-of-towners at the Port Authority Bus Terminal or airport, and take them to breakfast at a midtown diner.

As a nurse, Ms. Pippins could answer their medical questions. As a mother, and someone from a conservative Southern upbringing, she could relate to their fears and concerns of being ostracized back home.

“At that time, you were shunned if your son died of AIDS, or you had AIDS in your family,” Ms. Pippins told NY1 in 2010. “And I wanted to get together and let them know there was other people having the same problem.”

For Ms. Pippins, her work with AIDS patients was redemptive. “I needed to give back,” she told Mr. Kroot. “I needed to have something to do that made me feel better about me.”

Jessie Juanita Pippins was born on Feb. 2, 1927, in Dothan, Ala., to Alto Lee and Junie Roberts. Her father was a cotton farmer and wanted his daughter to stay on the farm, Ms. Pippins told Mr. Kroot.

She was not interested. She pestered her father to let her study nursing at Florida State University until he relented. She became a registered nurse, and later director of nursing at a hospital in Pensacola. She retired in 1981.

She and her first husband, Joseph Pippins, divorced. A second marriage, in effect arranged by her son so she wouldn’t be alone after he died, was short-lived. Her survivors include a stepdaughter, Kelley Pippins Hays, and three step-grandchildren.

In her second life as a New Yorker, Ms. Pippins attended Broadway shows and dined out with friends like Mr. Kroot and his husband, Anthony Catanzaro. Other friends from her son’s circle took her on vacation with them to London. The group remained bonded for decades.

Ms. Pippins, who was present at the end of life for so many during the AIDS crisis, died alone on Mother’s Day.

Ms. Pippins, a retired nurse living in Pensacola, Fla., put her belongings in a friend’s house, took what she could and moved to New York to care for her son. At age 60, she began an improbable and remarkable second act.

Devastated and ashamed by her son’s AIDS diagnosis, and troubled that he was gay, Ms. Pippins initially kept the illness a secret from her family and friends. And she felt out of place in the big city. On breaks while caring for her son, with whom she had moved in, she would sit inside the Nathan’s Famous restaurant then in Times Square and repeat, “I hate New York. I hate New York. I hate New York.”

But Ms. Pippins nursed her son for three years as AIDS ravaged his body and he went in and out of the hospital. She saw members of the theater group he had founded and residents of their midtown building, Manhattan Plaza, falling sick also. And by the time her son died, in 1990, Ms. Pippins had been transformed.

She became close with her son’s gay friends, and decided to stay in New York. She dedicated herself to AIDS causes. She became a tireless volunteer for Miracle House, a charity that provided out-of-town families of AIDS patients with housing and support.

For mothers working through anger, guilt and sadness, Ms. Pippins served as a parent who had been there. For men estranged from their families, she became a replacement mother, sometimes holding their hands as they died.

“She didn’t come here to be an activist,” said Irwin Kroot, who met Ms. Pippins through her son’s partner, Dennis Daniel, and interviewed her for a possible memoir. “She was filling a void. She was usually with young men who were dying and was, at their request, a go-between for them and their families.”

Ms. Pippins died on May 10 at Amsterdam Nursing Home in Manhattan. She was 93. The cause was complications of the novel coronavirus, Mr. Kroot said.

At a time when AIDS was widely misunderstood and gay men who suffered from the disease were treated like pariahs, Ms. Pippins called on countless families across the country to come visit their children. Often, those parents had little sense of their sons’ lives in the city or how sick they were.

Ms. Pippins would tell them to set aside differences and be present for their child. Some took her advice, some didn’t. Ms. Pippins would meet wary out-of-towners at the Port Authority Bus Terminal or airport, and take them to breakfast at a midtown diner.

As a nurse, Ms. Pippins could answer their medical questions. As a mother, and someone from a conservative Southern upbringing, she could relate to their fears and concerns of being ostracized back home.

“At that time, you were shunned if your son died of AIDS, or you had AIDS in your family,” Ms. Pippins told NY1 in 2010. “And I wanted to get together and let them know there was other people having the same problem.”

For Ms. Pippins, her work with AIDS patients was redemptive. “I needed to give back,” she told Mr. Kroot. “I needed to have something to do that made me feel better about me.”

Jessie Juanita Pippins was born on Feb. 2, 1927, in Dothan, Ala., to Alto Lee and Junie Roberts. Her father was a cotton farmer and wanted his daughter to stay on the farm, Ms. Pippins told Mr. Kroot.

She was not interested. She pestered her father to let her study nursing at Florida State University until he relented. She became a registered nurse, and later director of nursing at a hospital in Pensacola. She retired in 1981.

She and her first husband, Joseph Pippins, divorced. A second marriage, in effect arranged by her son so she wouldn’t be alone after he died, was short-lived. Her survivors include a stepdaughter, Kelley Pippins Hays, and three step-grandchildren.

In her second life as a New Yorker, Ms. Pippins attended Broadway shows and dined out with friends like Mr. Kroot and his husband, Anthony Catanzaro. Other friends from her son’s circle took her on vacation with them to London. The group remained bonded for decades.

Ms. Pippins, who was present at the end of life for so many during the AIDS crisis, died alone on Mother’s Day.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario

Nota: solo los miembros de este blog pueden publicar comentarios.